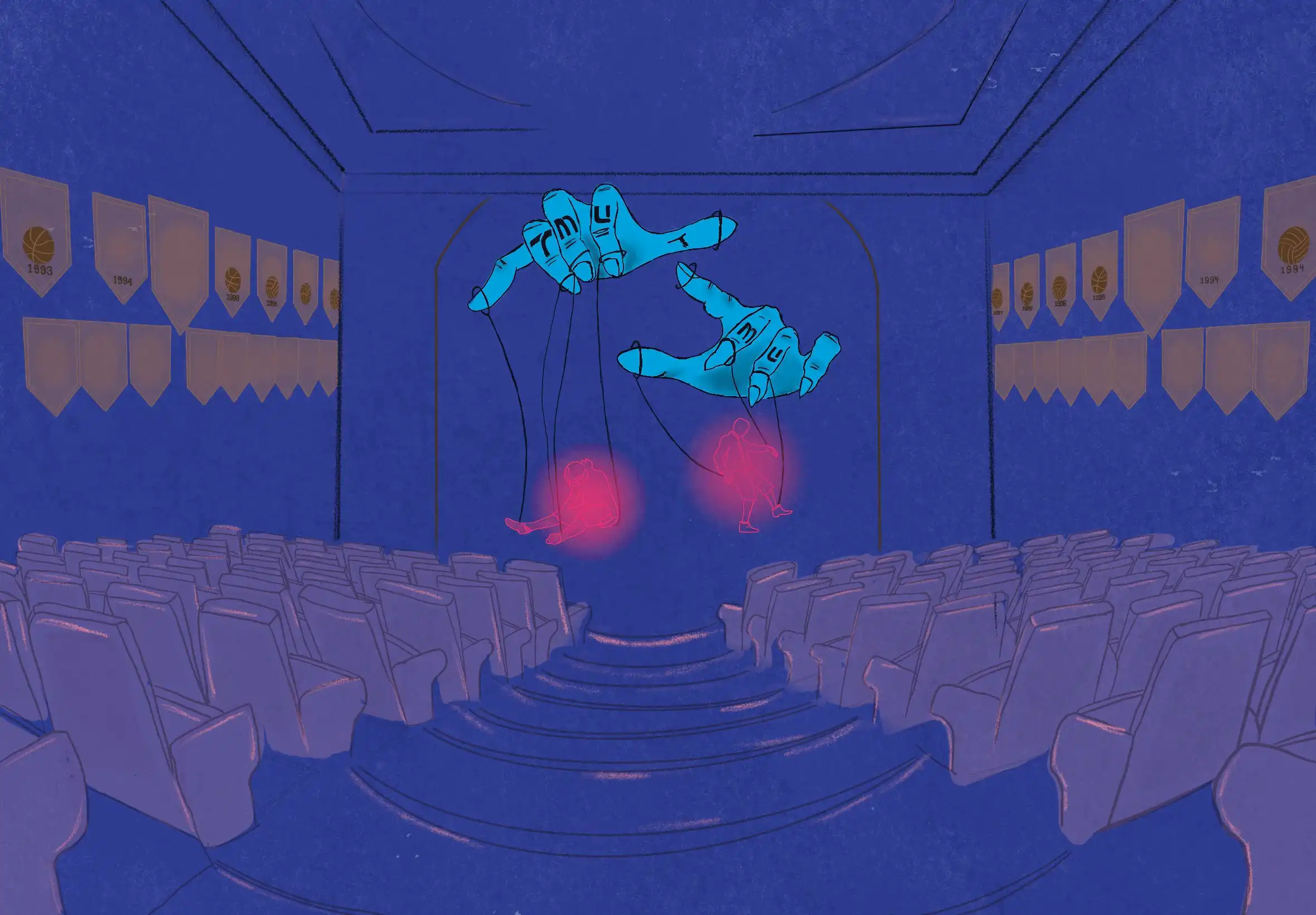

Sport is powerful. It has the ability to bring people together, push change and inspire future generations. However, sport also has the power to distract.

Whether you’re a casual or avid sports fan, the term “sportswashing” may be unfamiliar; nonetheless, you’ve probably watched a “sportswashed” event. Hailing from greenwashing and whitewashing,

the term is said to have been first coined by Twitter users more than 10 years ago.

Sportswashing is the use of sport to help a nation’s reputation by giving it more influence and power on the global stage, says Alan McDougall, a history professor at the University of Guelph and an expert in sports history. Popularized in 2018 by Amnesty International, the human rights organization

says sportswashing “is where states guilty of human rights abuses invest heavily in sports clubs and events in order to rehabilitate their reputations.”

“Sportswashing, in terms of positives for the regimes that engage in it, is a relatively easy way of getting your brand and country’s name on the world stage,” McDougall says. “Once the sporting event starts, a lot of the criticisms fall away.”

In 2022 many sportswashed events took place—from the 2022 World Cup to the LIV Golf League and the 2022 Winter Olympics. The term reached

peak popularityon Google searches one week before the start of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar—but sportswashing isn’t new.

The idea dates back all the way to the 1936 Summer Olympics, also known as the Nazi Olympics. Adolf Hitler used the games to promote his government and spread antisemitic ideals, per the

Holocaust Encyclopedia. Many Jewish athletes were barred from participating, though nine Jewish athletes or athletes of Jewish parentage did win medals.

Perhaps the biggest juxtaposition to Hitler’s games was American track star Jesse Owens. As the most successful athlete at the Games, Owens—a Black man—contrasted Hitler’s ideology of Aryan supremacy.

While the concept of sportswashing has been around for almost a century, it’s unclear just how many people have heard the term or know of the concept.

“I hadn’t heard of the term until the World Cup came,” says Tasala Tahir, a sports industry professional and instructor at Toronto Metropolitan University’s (TMU) School of Journalism. “The actual practice, that’s just been something I think everyone almost knows but you never know what to say about it.”

McDougall says there are two ways sportwashing can occur: either through hosting a major sporting event, such as the World Cup or by taking ownership of individual teams or leagues like the LIV Golf League.

A prominent and most recent

‘sportswashed ’ event was the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, skeptics say. The

discourse surrounding the 22nd World Cup began years before the small gulf country was set to host it. It was rumoured that Qatar paid FIFA officials £3 million to secure their bid; however, after an investigation, the country was cleared of any wrongdoings,

per the BBC.

Qatar

reportedly spent over $220 billion to build infrastructure for the tournament. Yet, the cost wasn’t the biggest issue. 95 per cent of Qatar’s workforce is made up of migrant workers, mostly from India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Kenya and the Philippines, according to

Human Rights Watch.

The Guardian reported that between 2010 and 2020, 6500 migrant workers died due to unsafe working conditions. Yet a comment from Qatari officials regarding the death toll was scarce. In one instance, a

Qatari official revealed between 400 and 500 migrant workers died in the last 12 years due to construction in preparation for the World Cup.

For some fans, it may be hard to ignore all the wrongdoings of an event or league, especially when it’s in the news so much. However, fans’ love for sport can also make it easy to forget.

Tahir says she’s often thinking about how an event may be sportswashed when she’s watching it. “Sometimes it makes me watch things and [other times] it makes me not.”

McDougall believes most fans who watch sporting events are aware of the sportswashing taking place behind the scenes. When watching a sportswashed event, he says many fans know it's wrong but their love for the game keeps them tuning in—he refers to this as cognitive dissonance.

The 2022 World Cup was arguably one of the most entertaining due to the quality of play and dramatic ending.

“Last fall, I watched the World Cup just like everyone else, fully knowing the context of everything going on,” said Mike Brock, a sports TV producer and a contract lecturer at TMU’s RTA Sport Media program.

“I’m absolutely guilty of being aware and educated on [the issues] but still compartmentalizing [them].”

Despite the alleged sportswashing tactics of the Qatari government, the 2022 World Cup broke records.

According to FIFA, close to 1.5 billion people watched the final compared to the 2018 World Cup’s 1.12 billion viewers. Meanwhile, around 3.4 million fans flocked to Qatar to watch the event live, compared to Russia’s 3 million spectators.

While the 2022 World Cup attracted global attention due to the claims of sportswashing, there are other events or teams that go unnoticed but still shape the narrative of a country or organization.

Paris Saint Germain F.C. boasts some of the world’s best male soccer players, from Kylian Mbappé, Neymar and Lionel Messi. However, Qatar Sports Investments

bought the club in 2011 and Paris has since become the top revenue-earning in France as well as in the world,

according to Deloitte. Moreover, the investment organization

bought a 22 per cent stake in S.C. Braga, a soccer team from Portugal, in 2022.

McDougall says in soccer particularly, “the fundamental fabric of the sport [has] been transformed, at least at the top level of European football.”

In contrast, the LIV Golf League was “an attempt to restructure or recast golf to break apart these long-standing institutions” in the United States and Europe, he said.

The LIV Golf League is a professional golf tour that emerged in June 2022 and is funded by

The Public Investment Fund, the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia. Human Rights Watch

criticized the league for using sport as a way to “‘sportwash’ ongoing abuses committed by Saudi authorities,” including execution, the suppression of peaceful protest and maintaining the famine in Yemen.

Despite the controversy, the league continues to thrive. In 2022, sports streaming service DAZN agreed to a

broadcasting deal with the league before the first tour even began.

The

LIV Golf League was created as an alternative to the existing professional golf leagues—the PGA and European Tour. The formation of this new league

attracted attention —both good and bad from PGA players. Their interest was piqued, which caused the PGA Tour to

send a message : anyone who decided to play in the

other league would be banned from competing in PGA events. Nonetheless, many players flocked to the new tour simply due to the amount of money it offered.

In the LIV Golf League, the first-place winner

receives $4 million dollars, while the last-place finisher

receives $120,000. Notable players to join the league include Dustin Johnson, Phil Mickelson and Brooks Koepka. Johnson was

reportedly paid £100 million to join the league.

Given recent events, it’s easy to assume that sportwashing is confined to or practiced by Arab or Middle Eastern nations. However, McDougall notes it's important to mention sportswashing happens elsewhere. “Any hosting of a mega sports event like a World Cup or an Olympics, are in some ways, a sportswashing project,” he said. The Russian Doping Scandal, the Berlin Olympics and Mussolini hosting the World Cup in 1934 are all examples.

As sportswashing gains more media attention, the idea of reporting and being vocal about these issues ethically arises. Is it up to journalists to fairly report on the matter? Or can politics and sports be separated? Is it up to protestors to try and make society aware? Or does it fall upon the shoulders of the fans?

From a journalist’s perspective, Brock believes it’s up to each individual to decide what voice they want to have and how to use it. However, many factors determine whether a person can speak out, including knowledge, professional freedom and the ability to speak about these topics correctly.

Tahir offers a less-clear approach. “Nobody knows the right way to do this,” she says. “I don’t know if there is a right way…I am trying to figure that out myself.”

The effects of sportswashing will take time to measure, says McDougall, though the reactions to its effects on sport are varied.

Brock believes that the integrity of the game won’t be affected and instead, it will be the athlete’s integrity that is challenged, though it depends on the situation. The integrity of those who choose to play in leagues such as LIV Golf differs from those who choose to represent their country on the Olympic stage.

McDougall thinks the integrity of sports is questioned. “I think it helps make the rich richer and the poor poorer in elite sport.”